POSTS |CTF WRITEUP

Another part of my series of CTF write-ups from ADFCSC 2023, this time a fun little binary challenge

| Difficulty Rating | Satisfaction Rating |

|---|---|

| Low | High |

Setup

Do you know how a string works?

Okay, that’s not exactly what the setup was, but it was essentially: “here’s a binary, the flag is in it, go have fun.” And that is what we are going to do!

We are given 1 file:

challenge-29D_ZalT.zip

This inflates to:

- challenge

$ file challenge challenge: ELF 64-bit LSB pie executable, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2, BuildID[sha1]=1b5720d11951f3f8d71b6aab0ec3333fa727ec4e, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, stripped

Running the binary reveals the following prompt:

┌──(lilith㉿kali)-[~/adfctf/String theory]

└─$ ./challenge

===============================================================================

Welcome to a challange the most malware reverse engineers' encounter also every

second day, dealing with encoded strings. You need to staticly or dynamically

analyse this ELF binary to decode the password and recover the flag!

Good luck!

===============================================================================

ENTER PASSWORD:

Trying the a random password, such as “letmein!” yields the following:

ENTER PASSWORD: letmein!

===============================================================================

WRONG PASSWORD: Try Again.

===============================================================================

Lets crack open the binary in our choice decompiling tool, Ghidra. Just as in one of my other write-ups, Ransomware, this is a stripped binary. The result is that the binary is slightly harder to reverse engineer, but this doesn’t really serve to hinder us beyond a slight delay. I will leave the more generic Ghidra initialisation processes to be explained in the previously linked write-up, and instead jump straight to identifying the main function:

void processEntry entry(undefined8 param_1,undefined8 param_2)

{

undefined auStack_8 [8];

__libc_start_main(FUN_00101229,param_2,&stack0x00000008,0,0,param_1,auStack_8);

do {

/* WARNING: Do nothing block with infinite loop */

} while( true );

}

Just as before, Ghidra identifies the entry point of the program, and we are able to determine the main function by observing the first parameter to the __libc_start_main function, which is a function pointer of the actual main function. In this case, we can rename FUN_00101229 to main and click into it.

Immediately of note are the variable definitions in main:

local_168 = 0xef21025ac6200d67;

local_160 = 0xca020153c2347178;

local_158 = 0xfc5e726c;

local_154 = 0x412b;

local_148 = 0x7a5379074552027f;

local_140 = 0x68576b5210520955;

local_138 = 0x76577d75795c726e;

local_130 = 0x5652675a5b67025a;

local_128 = 0x31;

This pattern is typically observed when the compiler optimises and inlines an array or string into stack variables. Seeing as we have two distinct ‘chunks’, we may actually have 2 inlined arrays/strings here.

The program prints the previously seen welcome and introduction, then proceeds to read in the password:

fwrite("ENTER PASSWORD: ",1,0x10,stdout);

fgets((char *)password,0x100,stdin);

input_len = strcspn((char *)password,"\r\n");

password[input_len] = 0;

input_len = strlen((char *)password);

if (input_len != 0x20) {

fprintf(stdout, /* ... */, "WRONG PASSWORD: Try Again.");

exit(1);

}

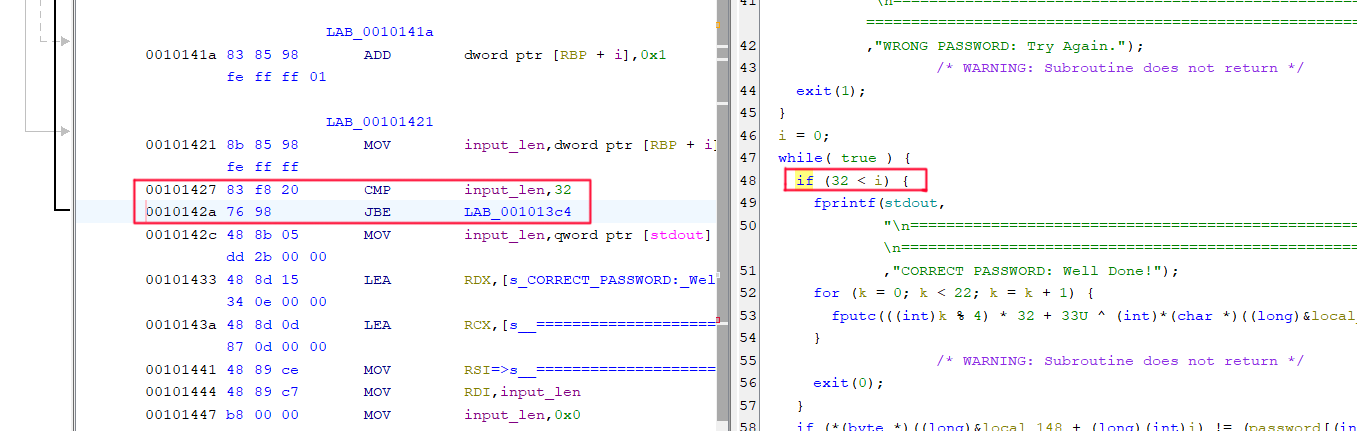

So already it looks like we can determine one property of the password: it must be exactly 0x20 (or 32) characters long, otherwise we suffer an early exit. So the next question is, how do we actually validate the password?

int i = 0;

while( true ) {

if (32 < i) {

fprintf(stdout, /* ... */,"CORRECT PASSWORD: Well Done!");

for (int k = 0; k < 22; k++) {

fputc((k % 4) * 32 + 33 ^ (int)*(char *)((long)&local_168 + k),stdout);

}

exit(0);

}

if (*(byte *)((long)&local_148 + i) != (password[i] ^ 49)) break;

i++;

}

So what actually is this loop doing?

- We loop forever, incrementing the counter variable

iat the end of each loop - if

iis greater than 32, we consider the password ‘correct’ and:- print 22 characters to

stdout, where - each character is a transformation of the current character, XOR’d by a byte from the previously mentioned inlined arrays/strings.

- Once complete, exit. We assume that these 22 characters are the flag.

- print 22 characters to

- otherwise, if the current

ith byte of the user input password, XOR’d by 49, does not equal theith byte of the other of the two inlined arrays/strings, break the loop.

This tells us two things:

- The password is not connected with the flag value whatsoever (i.e. the password is not the decryption key for the flag)

- The program assumes that if you stay in the loop for at least 32 iterations, such that

inow equals32or more, the password must be correct.

This opens up many avenues for binary modification and/or engineering to trigger the flag printing loop, some are:

- Run the program in GDB, putting a break point on the comparison operation for the if condition inside the while loop, and set the value of the given register to the expected value each time, or better yet

- Run the program in GDB, putting a break point immediately at the start of the while loop, and set the value of the

ivariable to 32 to trigger the flag print straight away. - Hexedit the binary to invert the if condition, such that it only breaks the loop if the input character is correct, rather than incorrect.

- Hexedit the binary to jump directly to the address of the flag printing loop upon entering the main function.

- Hexedit the binary to modify the condition of the first

ifstatement to trigger wheniis, say, 0.

Seeing as the binary is stripped, and ever so slightly more annoying to deploy breakpoints in GDB, we are going to employ our greatest skills as computer scientists: laziness.

We are going to perform the smallest possible modification to get the flag, and one that requires the least effort from us. If we employ our experience and new-found skills from the previously linked write up, it can be quite simple to invert the condition on an if statement with binary editing, in fact it came out to a single-byte change last time!

Because of the various compiler optimisations and the strange loop layout, it can actually be quite hard to determine which is the correct cmp/jXX opcode-pair we are looking to modify. But Ghidra, as always, continues to make this incredibly easy for us.

Here we can see a CMP followed by a JBE.

| Instruction | Description | Flags | short jump opcodes | near jump opcodes |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| JE | Jump if equal | ZF=1 | 74 | 0F 84 |

| JZ | Jump if zero | ZF=1 | 74 | 0F 84 |

| JNE | Jump if not equal | ZF=0 | 75 | 0F 85 |

| JNZ | Jump if not zero | ZF=0 | 75 | 0F 85 |

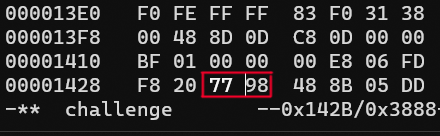

| JBE | Jump if below or equal | CF = 1 or ZF = 1 | 76 | 0F 86 |

| JA | Jump if above | CF = 0 and ZF = 0 | 77 | 0F 87 |

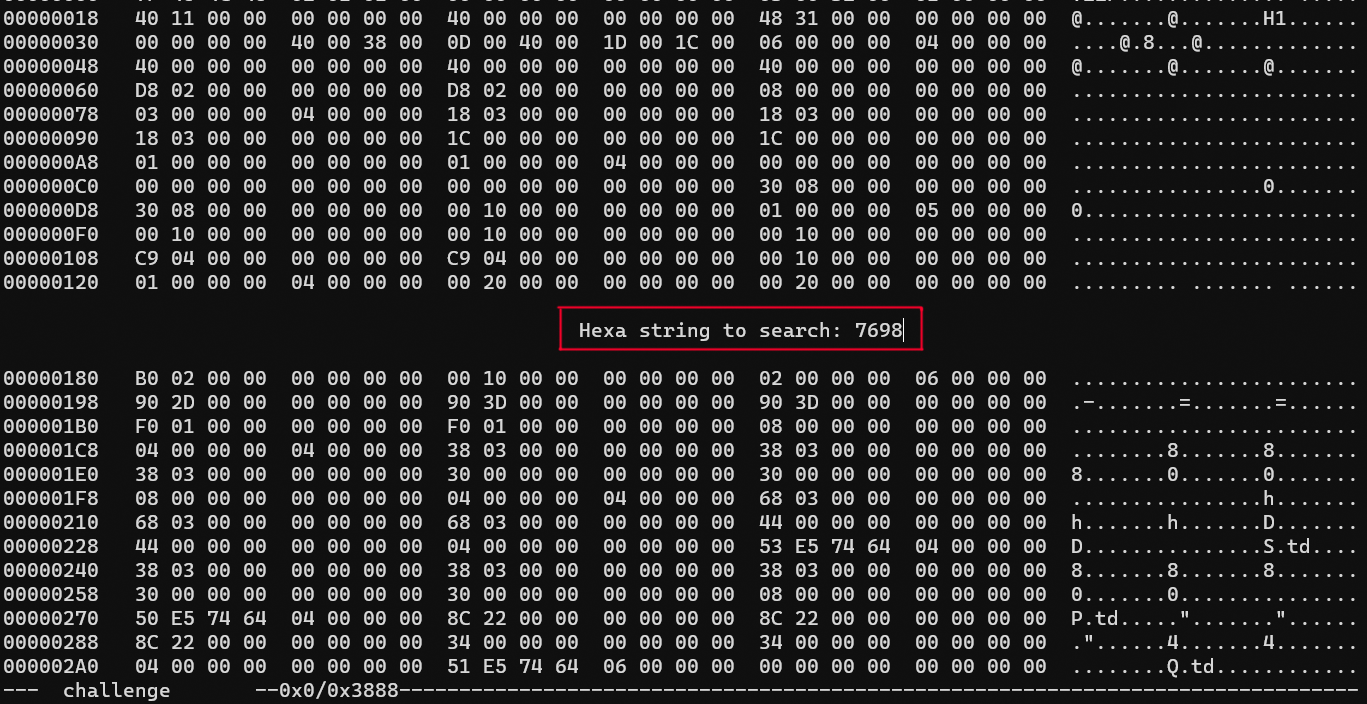

Again, we grab his Intel x86 Quick reference table from Steve Friedl. We can see that a JBE opcode equates to a ‘jump if below or equal’, of which the opposite is ‘jump if above’. Thus, we should be able to invert the condition of the if statement by converting the JBE to a JA. This would only require a single byte change, just as previously. Now, as this is a very specific short jump in a small program, we can fairly safely assume that the opcode 76 98 of the JBE instruction will only appear once in the program. Then we can simply change this to a 77 98 and have the if statement jump control flow into the flag printing loop when false, instead of the other way around.

Now, before we get trigger-happy and run the program, remember that there was an additional check right at the start that the password was exactly 32 characters long, so in the password prompt we will still need to enter 32 characters to satisfy that condition.

┌──(lilith㉿kali)-[~/adfctf/String theory]

└─$ ./challenge

===============================================================================

Welcome to a challange the most malware reverse engineers' encounter also every

second day, dealing with encoded strings. You need to staticly or dynamically

analyse this ELF binary to decode the password and recover the flag!

Good luck!

===============================================================================

ENTER PASSWORD: aaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaaa

===============================================================================

CORRECT PASSWORD: Well Done!

===============================================================================

FLAG{C@nY0UCr@cKM3?}

Great job!

So to recap:

- We decompiled the binary to understand how the password plays into the flag

- After determining the password value was irrelevant to the flag value,

- We theorised the smallest possible change to make to jump straight to the flag printing and skip the password checking

- ???

- profit